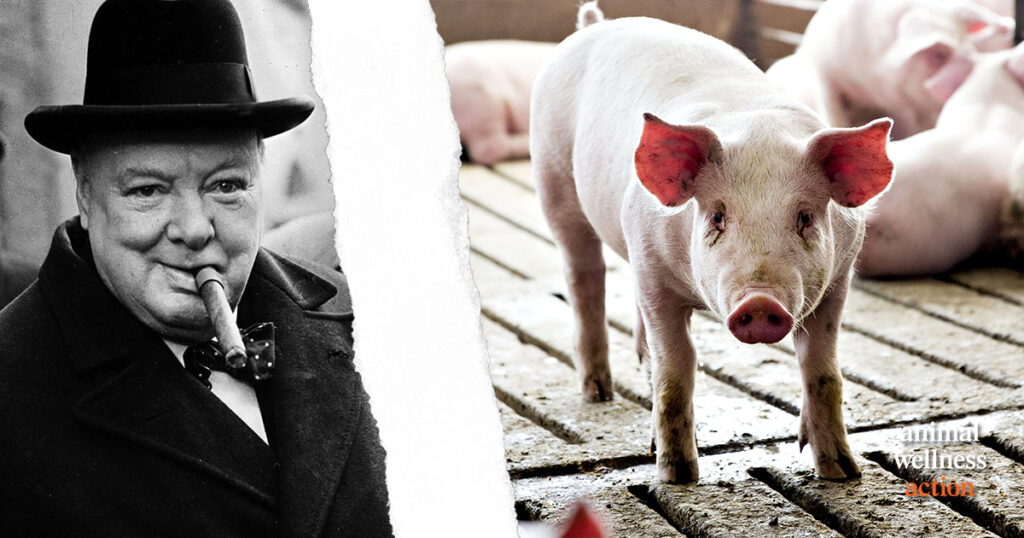

Sir Winston Churchill may have missed the mark by more than a few decades, but his vision for the future of food was characteristically bold and accurate. “We shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing, by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium,” he wrote in an essay in 1931. “Synthetic food will … from the outset be practically indistinguishable from natural products.”

Cellular or “clean” meat and leather are disruptive ideas, calling for changes throughout the entire food and textile industries. But are they any less fantastic than factory farming itself — a relatively recent innovation in food production that puts millions of animals meant to move, in cages in windowless buildings and altering their physiology to make them fast-growing meat machines?

In nature, digested grass produces flesh for meat and skin for leather, and it seems reasonable that plants can also provide the fuel for the growth of animal products in a controlled setting. Whether vegan or omnivore, you may have the option sooner than you think to eat a piece of meat that did not come from a full-bodied animal.

In the marketplace right now, diners already have a doppelganger for conventional meat. Plant-based burgers, hot dogs, chicken strips, fish-fillets, and tuna have grabbed real estate on store shelves and menus, and have replicated the taste and texture of meat without the moral stench of the factory farm. Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods are the best-known players in the plant-based space, but the big brands in food production and retail, including Cargill, Nestle, Kellogg’s, and even Tyson, are in on the action.

Meat isn’t going away soon. It’s always been part of the human story. But the future, to paraphrase the iconic 20th-century leader Churchill, may be here before we know it. Its downfall may come, as most things do, from a range of coincident causes, from innovations that mimic its taste to the triggering of our survival instincts because of its collateral effects to a rising tide of moral concern about animals.

President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act last week, declaring the meat industry “essential” after COVID-19 cases spiked at slaughter plants. That directive may be more rhetorical than practical, since the facilities may not be able to keep enough staff on the lines and the carcasses moving. More than 1000 workers contracted Covid-19 at the Tyson facility in Iowa. You cannot flatten the curve by exposing your workforce to a contagion and sending them back out into the community and into the hospital wards.

Here’s the problem: the modern meat industry never got the memo on any kind of normal social distancing. They put the close talker or the tailgater to shame. At production facilities, Big Ag giants confine animals nose to nose or beak to beak, in many cases unable even to turn around. At slaughter plants, they put workers shoulder to shoulder as well, as they exercise their repetitive motions in disassembly lines. Is it any wonder that disease festers in these environments?

Every year, one in six Americans — for a total of nearly 50 million cases — contracts foodborne illness. Factory farms contribute to a majority of those cases, including Campylobacter and Salmonella bacteria in poultry, Toxoplasma gondii in pork, and Listeria bacteria in deli meats and dairy. To this list, add bird flu, swine flu, Mad Cow Disease, and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a life-threatening bacterial infection that is immune to commonly used antibiotics in human medicine. The CDC estimates there are 23,000 deaths a year from antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Then add in the other “externalities.”

The meat industry’s captive animal populations discharge unfathomable amounts of animal waste, swamping the environment with untreated feces and urine from 9 billion animals raised and slaughtered every year.

If a soiled environment doesn’t induce illness, then there is the corrosive effect of eating too much of the commodity itself. High rates of meat consumption produce hardened arteries, stroke, heart attacks, and several varieties of cancer. These diseases afflict millions of people every year, and that’s precisely why the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and so many other health-oriented authorities urge people to eat more plant-based foods.

Because of COVID-19 outbreaks that caused meat plants to suspend operations — creating a backlog of animals who’ve reached market weight at the farm — the industry has resorted to mass “depopulation” of farm animals because of limitations on space and feed.

In a new essay published on National Review Online, essayist Matthew Scully laments the killing both inside and outside the slaughterhouses:

If ‘mass depopulation’ makes for a sickening sight, even to factory farmers, then you would think that “mass confinement” of animals would long ago have had a similar effect. Under ‘intensive confinement’, another term of the trade, these culled animals have known a world of only concrete and metal, with all the privations, mutilations, and other cruelties that are the industry’s first resort, and with even the veterinarians hired only to refine the punishments. Indeed, every modern hog farm is a training ground in culling, as the weak and near-dead are routinely dragged to “cull pens,” while the others are kept alive, amid pathogenic disease and squalor, only by a reckless use of antibiotics. The externalized cost to public health being left, as always with factory farming, for others to deal with.”

The meat industry is “essential” only to some of the people drawing pay from it, and most certainly not to the workers heading for the ventilators. It’s most definitely not essential for our health or that of the planet, given the massive load of greenhouse gas emissions created by animal agriculture. Add in the plural threats to our health from coronary diseases, viruses, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and you have something closer to a menace to society rather than a requisite of it.

As Scully concludes, in juxtaposing the mass cullings with the standard operating procedures of the meat racket, it’s a system “just as merciless when it is working to perfection.”