Heavy Thoughts About Lead Hunting

Millions of hunters continue to disperse thousands of tons of lead into the environment, putting people in jeopardy and causing pain and death for wildlife

- Wayne Pacelle

Nobody should use bullets that keep killing long after discharged from a firearm.

But that’s exactly what happens when hunters load lead rounds into their shotguns and rifles, take aim at their quarry, and scatter lead throughout the biotic community.

Think of 10 million hunters, fanning out across America’s forests and fields, hitting and missing quarry. Acting independently but with dangerous cumulative impact, they inject wild animals and pollute the wild with toxic bullets and fragments on more than a billion acres of public and private lands.

When a hunter dresses out a deer, elk, moose, or pronghorn, he takes the edible portion of the animal home for friends and family. If he’s used lead, the carcass will be riddled with toxic fragments, many of them too small to spot and remove.

The hunter need not ask the consumer — family, friend, or foodbank customer — if they want lead with their venison. It’s infused in meat and marrow.

But that’s just the half of it.

At the kill site, he also leaves behind the skin, sinew, bones, blood, organs, hooves, and other parts of the animal’s body — a “gut pile” that is a smorgasbord for denizens of forests. Eagles, vultures, foxes, and other species swoop in for a meal. There’s no waste in nature. The animals, in the circle of life, grab and go. Lead and all.

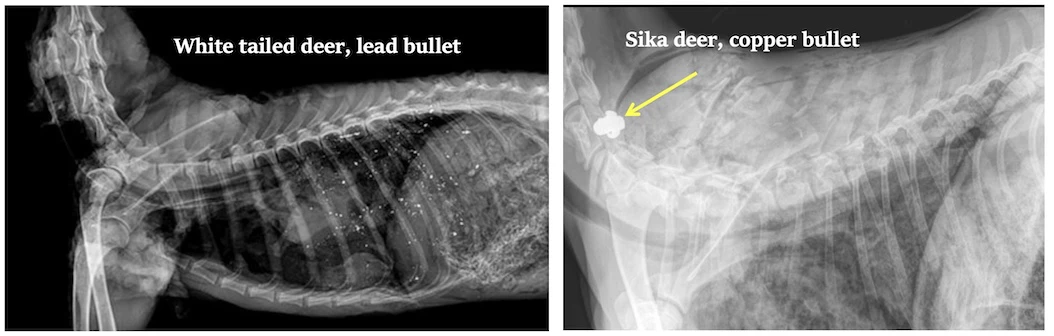

X-rays show the problematic disbursement of fragments from a lead 30-caliber Winchester magnum lead core with copper jacket compared to the single remnant of a solid copper bullet of the same caliber.

X-rays show the problematic disbursement of fragments from a lead 30-caliber Winchester magnum lead core with copper jacket compared to the single remnant of a solid copper bullet of the same caliber.

The Eagle Has Landed—With a Thud

A study published in January 2022 in the journal Science documented mass poisoning of eagles by ingesting lead ammo fragments, with population-level effects on these iconic raptors.

The eight-year study of 1,210 bald and golden eagles across 38 states — co-authored by dozens of wildlife scientists — determined that up to 47% of eagles had “bone lead concentrations above thresholds for chronic poisoning.” According to the study, a third of eagles had “acute [lead] poisoning.”

There may be more than 20 million wild animals of all species who die every year from lead poisoning, with the ground-feeding birds mistaking the lead fragments for seeds, and predators and scavengers consuming the remains. Known as plumbism, lead poisoning is painful, and even when lead exposure isn’t immediately lethal, it doesn’t take much to weaken an animal to the point that it succumbs to predation or disease.

The scientific and anecdotal evidence is as attention-getting as a 21-gun salute: Ingestion of lead bullet fragments has been the leading cause of death for the highly endangered California condor. Ingestion of lead bullet fragments is the leading cause of high lead blood levels in families relying on the meat of wild animals. And ingestion of lead bullet fragments is a leading reason raptors, vultures and other animals are brought to wildlife rehabilitation centers. Symptoms include deadened eyes, drooping heads, and quivering bodies.

Lead Is Not Meant to Be Ingested by Any Living Creature

With an atomic number of 82, lead has had its poisonous characteristics on display for more than 2,000 years. Its intrusion into the body has the potential to diminish the function of every organ. But plumbism is best known for its effects on the brain and cognitive function.

According to one peer-reviewed study published in 2022 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, exposure to leaded gasoline lowered the IQ of about half the population of the United States. The study focused on people born before 1996 — the year the U.S. banned gas containing lead.

“[Plumbism] can lead to a variety of neurological disorders, such as brain damage, mental retardation, behavioral problems, nerve damage, and possibly Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and schizophrenia,” according to the National Institutes of Health.

For these reasons, lead has been banned for use in toys, paint, gasoline, and other commercial products.

But state wildlife agencies — often repeating the mantra that they engage in science-based wildlife management — continue to allow and excuse lead bullets in all states but one. In California, state lawmakers deflected arguments from the guns and ammo lobby — without a single hunting group in favor — and passed a bill to ban lead ammo in 2013. The phase-in of non-toxic shot was completed in July 2019. The transition, more or less, has been seamless. And sales of hunting licenses have increased.

More than a generation ago, also over the objections of the National Rifle Association (NRA) and other extreme hunting groups, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service banned the use of lead ammunition in waterfowl hunting in 1991. “Plumbism [lead poisoning] was first seen in ducks in 1874,” wrote conservation writer Ted Williams. “But it wasn’t until 1991 that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service got around to banning lead shot for waterfowl.” The ban is estimated to have saved as many as 1.4 million mallards a year, along with perhaps a million other migratory birds.

That shift in policy is one of the great animal welfare and conservation success stories in 20th-century American wildlife management. But supposed leaders in the hunting community, quick to hold up a banner as conservationists, have often acted as impediments to halting the use of poisonous ammunition.

Here are just a few facts:

- Copper, steel, tungsten, and other elements and alloys are widely in use by hunters who do believe that they should only kill to eat and not leave a trail of other victims in the forests in the weeks after their hunting excursion.

- Non-toxic ammunition has plenty of killing power. The U.S. Army now uses only non-lead ammo for all of its small caliber weapons.

- There are more than 130 species of wild animals who perish from spent lead.

- Ammo companies introduced copper bullets in the mid-1980s — not to prevent plumbism in wildlife, but to kill game more effectively. As the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) reports, “Fortunately, today’s harder copper and other copper alloy bullets and [shotgun] slugs typically remain intact on impact, transferring more energy to the target by folding downward into ‘petals’ that greatly expand the surface area. The result is a very effective, quick, humane kill.”

It’s all so thoroughly preventable. Just use the wide range of alternatives.

But sadly, the NRA contrives a conspiracy even when it’s in its self-interest to seek reform. Poke around on the websites of the biggest ammo manufacturers, and even there you’ll find the firearms industry singing the praises of lead alternatives. “Looking for premium performance without the premium price?” asks one brand-name maker of steel shot. Others note that steel ammo “delivers denser patterns for greater lethality and is zinc-plated to prevent corrosion.”

Sport hunters often proudly cite the legacy of President Teddy Roosevelt, perhaps one of our nation’s best-known conservationists and hunters. Roosevelt understood that “conservation” is call to practical action to safeguard wildlife and the environment. Today’s hunters who use lead don’t get a pass for the wreckage of today by associating themselves with a conservation-minded hunter of yesteryear, especially one who died more than a century ago.

This week, I’ll appear with other animal advocates, wildlife rehabilitators, rank-and-file responsible hunters, zoo and aquarium leaders, and environmentalists to ask a key Maryland state legislative committee to start the process of making the Free State the second state in the nation to phase out lead ammunition. And soon, we’ll see lawmakers in Congress introduce legislation to ban the use of lead ammunition on our national wildlife refuges.

It’s hard to believe that these policies at the state and federal level even require debate, with 500 studies showing the toxic effects of lead ammunition on wildlife and humans. But such is our task — often to state the obvious, to overcome selfishness and greed, to demand better in our treatment of animals, and to ask the people in power to act without fear or favor.

Dear reader: If you support substantive policy work to protect animals, please consider donating to the Center for a Humane Economy today. You can give any amount one time, or make it a monthly gift, as many of our supporters do. Thank you for helping us fight for all animals. Please go here to make your contribution.