ReThink Mink

We are working to end mink farming for fur — an industry that causes immense suffering to mink and poses major animal and human health threats because of the unique susceptibility of factory-farmed mink to SARS-CoV-2.

The Issue

Until the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, American mink (Neovison vison) had been housed on factory farms for their dense, luxurious pelts in 36 countries, including the United States and Canada. About 90% of milk pelts produced in North America are exported to China, where they clothe a wealthy elite. There are three intertwined and important rationales to the effort to ban mink farming in the U.S.:

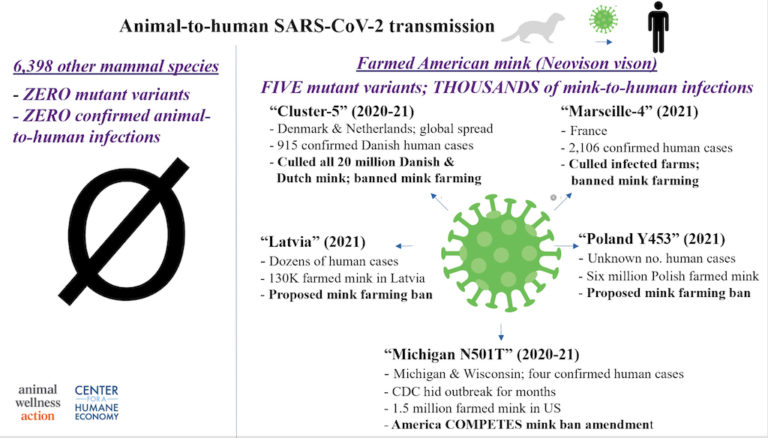

Mink are highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 and other zoonotic diseases such as influenza and antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as MRSA. COVID-19 outbreaks on more than 450 mink farms in 2020-21 across Europe and North America infected 7 million mink and killed 700,000 animals. Mink farm workers have repeatedly infected captive mink, and then infected mink then spilling the viral infection back to people, sometimes as dangerous mutant strains that resist human vaccines or treatment. Three dangerous mink-origin mutant COVID-19 strains emerged in Denmark, France and Michigan that infected thousands of people. Eighteen mink farms in Utah, Wisconsin, Oregon, and Michigan had SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks. At least one mink farmer died from COVID-19 acquired from working with farmed mink.

Mink are wild, undomesticated, solitary, unsocial, wide–ranging, and semi-aquatic carnivores. Perhaps even more than poultry, ruminants, or swine, they are totally maladapted to intensive industrial confinement. Housed in tiny wire cages in barn warehouses by the thousands, many injure, kill and even cannibalize weaker cage-mates until they are killed at just 8 months of age for their velvety pelts. Severe distress from unnatural living conditions and inbreeding for coat density and color multiplies zoonotic disease risk via immune suppression. Mink welfare and zoonotic risk cannot be disentangled.

Captive mink are athletic, clever escape artists that escape captivity by the thousands worldwide. Feral escaped mink are twice the size and more fecund than wild mink, so they can act like an invasive species to displace wild mink. They can also introduce new diseases to wild mink and other mustelids. Escaped, feral and wild mink infected with COVID-19 were trapped in Oregon and Utah which could lead to an ineradicable wildlife virus reservoir just as rabies, plague and brucellosis are entrenched in our wildlife populations. The highly endangered black-footed ferret, a mink first cousin, is at high risk from contact with diseased escaped or feral mink.

Leaders

There are about 60 independently owned mink farms in the U.S., concentrated in Utah and Wisconsin. The structure of the industry is similar Europe, but public health authorities and political leaders are seeking to ban the industry because of animal welfare and public health threats. Prior to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, Europe accounted for half of worldwide production, raising 30 of the 60 million captive mink in the world. There is also production in China and Russia.

Zoetis and Ceva, two global top 10 animal health companies, are the only companies that produce mink vaccines for the North American market and enable an industry that poses a biohazard to the world.

The Business Case

Farming of the American mink for their fur is a failed century-long experiment: “Nobody needs a mink coat but the mink.”

Mink farming begin in America after the Civil War to provide warm winter clothing for soldiers when wild mink populations had declined due to over-trapping. The captive-mink industry peaked in the 1960s and has been in steady decline since then. Today, virtually all clothing sellers and fashion designers do not work with mink any longer, and the number of independent fur stores has also declined precipitously. Consumers have ethical concerns about the mistreatment of animals and understand there are fashionable and functional alternatives.

The cost of raising a mink exceeded pelt value for most of the past decade. Just 60 active mink farms produced 1.4 million pelts in 2020 with farm-gate value of just $47 million. Mink farmers in some states (e.g. Utah) and the Canadian maritime provinces (e.g. Nova Scotia) rely on millions of dollars in government subsidies each year to survive financially.

Today, this is an industry producing a luxury product now for a tiny sliver of Chinese consumers, violating animal welfare norms and threatening animal and human health. Nobody needs mink pelts these days, and very few people want them.

Read More About Our Campaign

Read our report on Mink Farming & SARS-CoV-2

Actions to Take

Do not wear or purchase garments that contain real animal fur, even as trim.

Rethink buying veterinary products made by Zoetis and Ceva and express your displeasure.