The Center Calls for Buy-Out of American Mink Farms

It’s time to shut down the least-known and perhaps most appalling form of factory farming

- Scott Beckstead

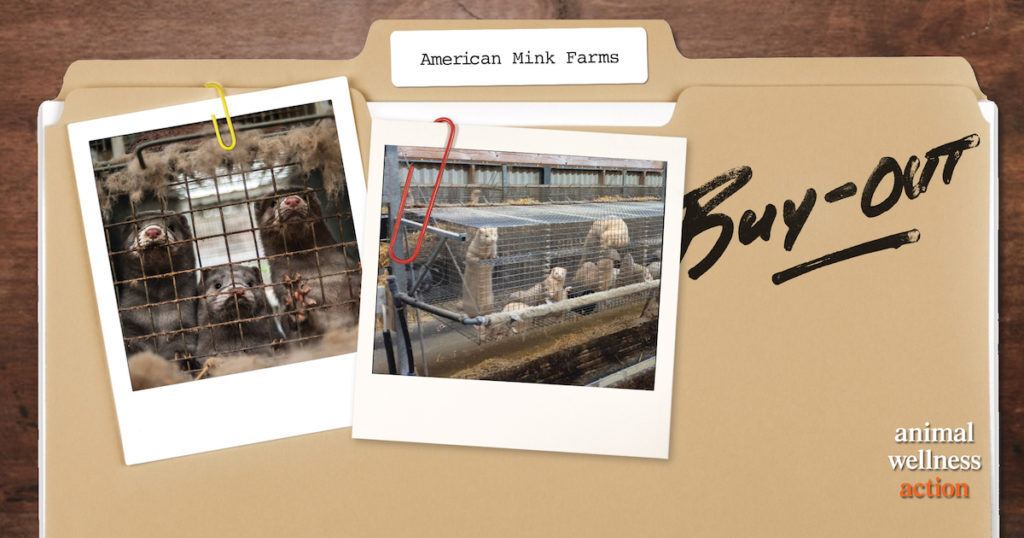

Drive into a complex of long, neatly arranged windowless building in Wisconsin or Utah or Idaho and, if you are able to push open a door and peer in, you might have to hold your nose and avert your gaze as you discover thousands of pigs trapped in small metal boxes or tens of thousands of broiler birds crowded shoulder to shoulder. But in these states, should you come across a confined animal feeding operation, you’d stand pretty good odds of getting a peak at the least known form of factory farming: the mass incarceration of mink, a carnivorous mammal in the same family as badgers and otters.

On first glance, you’d notice the crowding and an overwhelming stench, but perhaps also the aggression and other abnormal behaviors or their beautiful coats, from tawny brown to black, white, and silver blue — most of them intentional mutations made to create color phases you wouldn’t see in their wild kin.

It turns out that these wild-animal factory farms are COVID-19 hot spots. Unlike other nonhuman animals, mink are unusually susceptible to the virus, and in Europe and in the United States, they are dying en masse, given the filthy, crowded conditions on these factory farms, which provide a perfect environment for the virus to move with devastating speed from mink to mink in rapid-fire fashion; mink have no immune response to COVID-19 and typically die within 24 hours of the first symptoms. Public health officials are alarmed and mink farmers are reeling.

Mink Farm Outbreaks an International Crisis

This week, I wrote to U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue and asked him to work with governors in the big mink-farming states to begin the process of shuttering the farms and buying out the farmers. Our national health emergency warrants this kind of protective action. Mink farms are potential super-spreaders of the virus.

Europe appears to have had the first mink-farm outbreaks of COVID-19. There, mink by the millions perished, from the effects of the disease or from the culling that followed the outbreaks. According to one study, at least two farm workers have caught the virus from mink.

Driven mainly by the viral transmission concerns, but mindful of the long-standing concerns about the unsuitability of keeping semi-aquatic wildlife in extreme confinement and frustrate their instinct to live in and around water, government authorities announced plans for buy-outs of the mink farmers.

The Netherlands, which had previously agreed to shut down its massive mink industry by 2025, said it would accelerate the closure to take effect this year and dole out $200 million to the farmers to cushion the blow. Three weeks ago, France decided to phase out its farms. Poland, with more than 700 mink factory farms, is considering the same. Austria, the Czech Republic, and more than a half dozen other European nations had already banned fur farming based on humane treatment concerns. But Sweden and Finland, among others, are defiant, and political protests are expected to flare.

“When I grew up on a mink farm in Idaho, it was a significant and profitable industry,” Scott Beckstead, director of campaigns for AWA, told me. “Now, farms go belly up every year because pelt prices have crashed.” The total value of U.S. mink pelt sales has dropped from $291 million in 2011 to $59 million in 2019 — a five-fold decrease in just eight years. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the total number of pelts produced annually, however, has only dropped nine percent, from 3.1 million in 2012 to 2.7 million in 2019, meaning that mink farmers have had little drop in production costs but precipitous declines in total revenues. According to the Fur Commission USA, the trade group boosting the mink industry, there are perhaps more than 200 farms in the United States, with Wisconsin the top state, accounting for more than one-third of production, and Utah trailing close behind.

COVID-19 is just the latest crisis for the industry. For years, the industry has faced a different kind of viral threat — the person-to-person transmission of moral concern for the animals, killed for a luxury garment. In the U.S. and Europe – the two biggest markets in the world — we now have a form of moral herd immunity to the propaganda of the fur industry. And the moral concern has now spread to fashion designers, retailers, and consumers who shun fur. The result: the market for mink in the West has tanked, leaving the farmers in the U.S. and Europe to hunt for new buyers in far-flung parts of the world where the ethical concern for the animals has not infected the citizenry. It’s telling that at the industry’s annual premier fur auction in Canada last month, large volumes of pelts went unsold, and prices were at historic lows.

The grim irony is that many of the U.S.-produced mink pelts are bound for China.

This circumstance is a boon for the Chinese retailers and consumers with an interest in mink, but a viral time bomb for the United States. Just as it gets so much factory-farmed pork from the U.S., China is outsourcing mink production to the United States, and our communities are left to deal with the negative externalities, including assuming the risks of having super-spreader farms in their midst. I can understand why China loves this, but I cannot for the life of me understand why we allow this kind of asymmetrical arrangement to persist in our country.

National Mink Buy-out

AWA and its partners are calling for change, including a strict quarantine order at all mink farm operations. We recommend three other steps: 1) De-commercializing of mink farms, with no movement of non-essential products or workers to and from mink farms, including the movement of live animals on and off the farms; 2) A halt to breeding programs to arrest the expansion of host animals; and 3) A USDA buy-out of the mink farms, as a humane response to the circumstance of the producers.

The United States has already spent trillions on pandemic response. We are disrupting nearly every aspect of our economy to halt the virus, in the hopes of eliminating it or at least containing it to manageable levels until a vaccine is developed. In the scheme of things, it is a minor expense to buy out 200 mink farmers, whose total commerce is less than $60 million. That’s a rounding error in the COVID-19 relief packages.

So many ideas that were unimaginable 10 months ago are now being put into practice. And this one is not a close call when you bundle together the moral concerns about the industry, precipitously declining sales and a dim future for these producers, and the viral threats to our communities from farms selling a product Americans don’t want or need.

And consider this fictional mind-teaser: If China had a diabolical plan to stall the American economy, what better way for the country to stealthily deliver on that idea by buying up American mink pelts and keeping the mink farms operating, with the farms transmitting the viral load from mink to mink and then mink to man?

Don’t think about the mink buy-out as just an animal protection plan. Think of it as national security.